VOC: 1602 – 1798

(Verenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie – VOC); 1602 – 1798; area of activity: Indonesia, Moluccas, Japan (Nagasaki coast), Iran, Bangladesh, Thailand (formerly Siam), Guangzhou, China (formerly Canton), Taiwan (formerly Formosa) – to 1662, South India

(Verenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie – VOC); 1602 – 1798; area of activity: Indonesia, Moluccas, Japan (Nagasaki coast), Iran, Bangladesh, Thailand (formerly Siam), Guangzhou, China (formerly Canton), Taiwan (formerly Formosa) – to 1662, South India

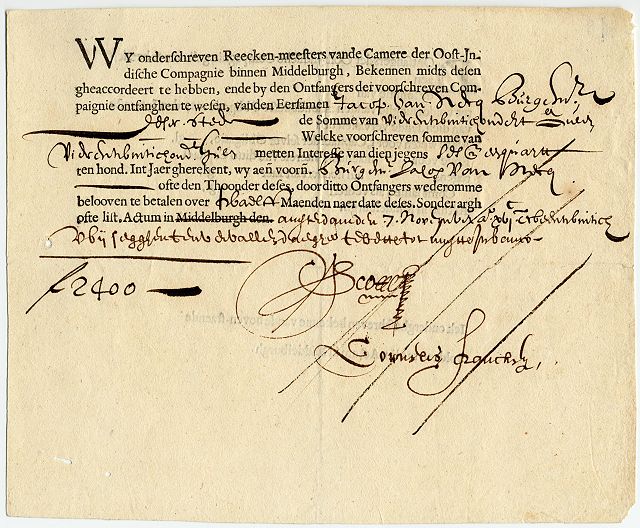

The VOC was a joint stock company, which raised funds for its activities by issuing shares (shared capital amounted to 6.5 million old guilders).

A VOC share

At the head of it stood 17 directors, so-called Lords XVII (Heeren XVII). The aim of the VOC was not territorial conquest, but the trade monopoly. Colonial expansion in the Far East took place at the expense of weakening Portugal and with a constant rivalry with Spain and England – the latter one constantly growing to strength. The stages of this expansion were as follows:

1605 – conquering the Ambon Island, and then next islands of the Archipelago of the Moluccas.

- 1619 – seizure of the part of Java and establishing there a city of Batavia

- 1624 – seizure of Formosa

- 1641 – seizure of Moluccas

- 1658 – withdrawal of the Portuguese Ceylon

- 1669 – seizure of Makasar

- 1682 – seizure of Bantam

The colonial activities of VOC applied three types of tactics:

- conquest and seizure of full territorial rule

- getting a monopoly on trade as a result of monopolistic agreements with local rulers

- negotiating agreements respecting the law of free competition from traders of other nationalities.

The most welcome was tactics No. 2

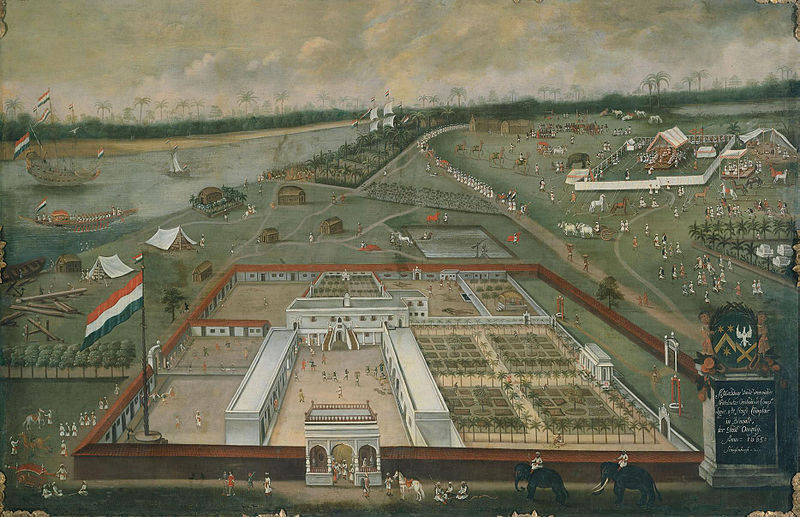

The city of Batavia (now Jakarta), established in Java, was a centre of very dense connections web, linking major cities in Asia.

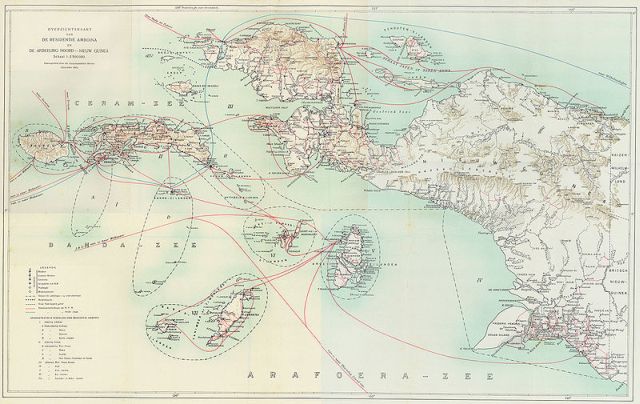

Commercial routes of VOC

In trade the Netherlands focused mostly on spices: pepper, cloves and nutmeg. In the areas, where VOC exercised territorial control, supplies were enforced by quotas, and price was imposed. Those suppliers who had not fulfilled their obligations were punishing by death or slavery (forced to work on plantations controlled by VOC). When prices felt down, the Dutch used to destruct plantations and even the product itself. On the other territories the goods were obtained through agreements with local rulers, who in return for supplies received “protection”. Of course they also derived considerable benefit from cooperation with Dutch merchants.

Dutch plantation in Bengal (Indie), Hendrik van Schuylenburgh, 1665

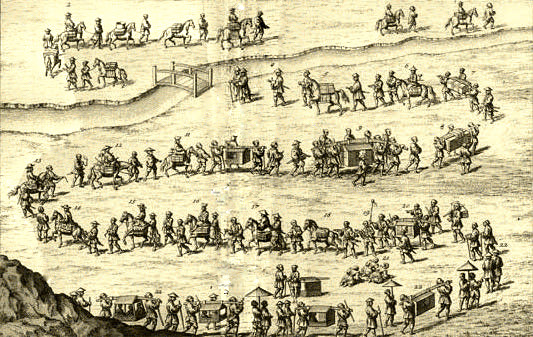

VOC also maintained commercial relations with Persia, Siam, Japan and China. Dutch merchant’s relations with Japan were for two centuries based on the privilege of exclusivity. This exclusive position was achieved thanks to avoiding the mistake of Dutch predecessors – Spanish and Portuguese. The Netherlanders didn’t try to operate namely missionary, and what’s more – the Japanese were told that they were not catholic Christians! But they were not allowed in the area of the Japan empire and had to stay in an artificial island Decima, which was specially built for them.

Interesting remark

Once a year the Dutch merchants were allowed to enter the territory of the empire under the pretext of submitting the emperor a tribute and respect (the Dutch referred to this as paying the tax) – the same ban was formally upheld. During this trip merchants had the opportunity of business meetings. Those trips were described in interesting reports which survived up today.

Dutch going to Edo to pay tribute to the Japan emperor, 1727

The same ban applied to China – direct trade began only in 1729, and Guangzhou became the place of the exchange. (Chinese were prejudiced against the Dutch because of the Portuguese, who presented them in a very negative way.) One of the goods obtained in those countries and exported to Europe was tea (the Dutch were the first who sent to Europe Chinese tea, what happened in 1610). Amsterdam was even in the 18th century the largest market for this commodity. VOC exported to Europe also porcelain. Attempts to imitate the famous Chinese porcelain gave impetus to creation famous Delft porcelain, which became very popular in Europe.

There were also strong trade connections with Arab countries – Saudi coffee was introduced in Europe by the Dutch. VOC was not shunned as the intermediary in trade between Asian countries, of which the company also derived enormous benefit. How big were those benefits show dividends paid to the shareholders. In the best period (the beginning of the 18th century) they were paid as much as 40%, and in long periods commision was between 15-25%.

VOC warehouse in Oostenburg, Amsterdam

Decline and fall of VOC occurred in a period of crisis of the Republic of the United Provinces (late 18th century). The official bankruptcy was declared in 1798, and then East India Company stopped to exist. Its archives are presently kept in the national archives, on the shelves of many kilometers in length. Besides the weakness of the United Provinces there were several more reasons behind it. A characteristic feature of the c olonization of the East Indies by the VOC was that it did not lead to a mass migration of the population of the Netherlands. Landless peasants inclined to seek happiness rather in other European countries than in the Far East (Europe was in the first half of the 17th century heavily depopulated). They didn’t care about rapid and easy career in colonies. VOC officials also were reluctant to leave Netherlands and often traveled to the East Indies only for the contract. Salary of the lower officials, soldiers, sailors and other professionals were so low that a large-scale smuggling flourished, illegal transactions, forged bills and corruption were very common. Over those distant lands the Republic of the United Provinces was unable to exercise effective control. And it was not without its fault, running politics of squeezing maximum benefit at minimum cost. This is why the Dutch colonies were under-funded, and having too little money for defense, could not effectively resist colonial rivals, mostly England. On the photo: VOC Amsterdam flag om a replica of 16th century ship “Amsterdam”.

olonization of the East Indies by the VOC was that it did not lead to a mass migration of the population of the Netherlands. Landless peasants inclined to seek happiness rather in other European countries than in the Far East (Europe was in the first half of the 17th century heavily depopulated). They didn’t care about rapid and easy career in colonies. VOC officials also were reluctant to leave Netherlands and often traveled to the East Indies only for the contract. Salary of the lower officials, soldiers, sailors and other professionals were so low that a large-scale smuggling flourished, illegal transactions, forged bills and corruption were very common. Over those distant lands the Republic of the United Provinces was unable to exercise effective control. And it was not without its fault, running politics of squeezing maximum benefit at minimum cost. This is why the Dutch colonies were under-funded, and having too little money for defense, could not effectively resist colonial rivals, mostly England. On the photo: VOC Amsterdam flag om a replica of 16th century ship “Amsterdam”.

Replica of the ship “Amsterdam” – video

Despite the scarcity of the European population, especially a decent white women (the one which migrated to the East Indies were mainly shrew), the Dutch for a long time avoided racial integration of indigenous people. Then they gradually accepted marriages with local women – Christians, and then non-Christians, but did not allow them and their children to enter territory of the Republic. They were no Dutchmen. Those who were born in Asia, regardless of race, had always been inferior to Europeans and had to give them way to the filling of offices and positions.

VOC was also active in Africa, what has been described in the chapter Colonies in Africa.

DUTCH INDIE – 19th CENTURY

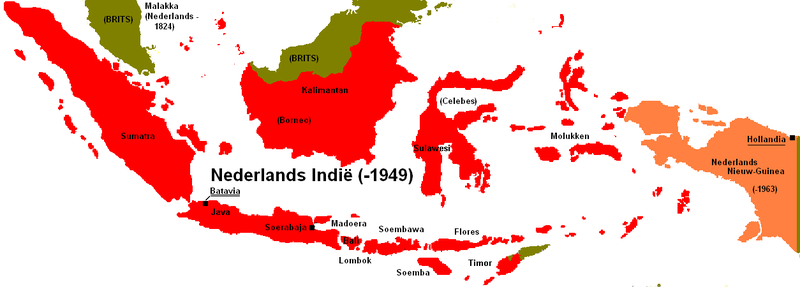

After the fall of VOC the situation of Dutch colonial territories varied. Ceylon and Malaya (1824) were irretrievably lost to England. The English hadn’t managed however to have Sumatra and Java islands under control , which were captured by them in 1811 for three years only, and in 1814 returned to the Netherlands. Since then, the former East Indies began to be called Dutch Indies. Since the creation of the United Kingdom of the Netherlands in 1815 until 1848 the sovereignty of the colonies was held by the king, and since 1848 it was given to the General States.

Dutch Indie

The fall of VOC and abolition of the trade monopoly, with increasing competition from England, forced the Netherlands to determine the new forms of exploitation of Dutch Indies. From now on peasants, under the new system cultuurstelsel (cultivation  system), had to spend 1/5 of their land for cultivation imposed on them by the Dutch, and the landless had to work on plantations for a 1/5 of the year. This system proved to be very effective and profits from selling sugar and coffee rose considerably. (Income from investments in colonies was spent in the Netherlands.) But in the mid-19th century, under the influence of liberal ideas, a certain part of Dutch society demanded reforms in the colonies: reducing state control and increasing freedom for private business. This led to legitimization of the activities of a private capital. It was introduced by the Government Regulations (Regeringsreglement) of 1870, which was in force until 1925. A significant change was the replacement of compulsory deliveries of agricultural products by taxes, such as the poll tax, land tax and indirect taxes. In the photo: a collection of resin from the tree Agathis dammar, Celebes.

system), had to spend 1/5 of their land for cultivation imposed on them by the Dutch, and the landless had to work on plantations for a 1/5 of the year. This system proved to be very effective and profits from selling sugar and coffee rose considerably. (Income from investments in colonies was spent in the Netherlands.) But in the mid-19th century, under the influence of liberal ideas, a certain part of Dutch society demanded reforms in the colonies: reducing state control and increasing freedom for private business. This led to legitimization of the activities of a private capital. It was introduced by the Government Regulations (Regeringsreglement) of 1870, which was in force until 1925. A significant change was the replacement of compulsory deliveries of agricultural products by taxes, such as the poll tax, land tax and indirect taxes. In the photo: a collection of resin from the tree Agathis dammar, Celebes.

Throughout the period of the presence of the Dutch in the Dutch East Indies some protests of the local population were breaking out. In 1825 an uprising took place in Java against the colonists, local rulers and Chinese merchants. This uprising lasted until 1830, but was bloodily suppressed – about 200 000 Javanese were killed. Another rebellion, including Sumatra, Sulawesi and Bali, were relieved by punitive expeditions. Local wars and conflicts were very common.

1873 was a year of the outbreak of the war with the sultanate of Aceh, located in the north of Sumatra. In the 16th and 17th centuries it was the most important country in the region. The sultanate used to support piracy but as long as it happened far away from the most important sea routes, VOC didn’t care much. The situation had changed after creation of the Suez Canal, which meant that ships had to pass along the coast of Aceh. This forced the Dutch to conquering of the sultanate, which led to a long and costly war (1873 – 1903), ending in the fall of the sultanate and control over the whole island by the Dutch.

Dutch officers in Aceh, 1900

Since about 1910 the Netherlands controlled already the whole Malay Archipelago, but the status of each area was different. More than half of the area had been included in the Dutch Indies; some part of it enjoyed some formal autonomy. Possessing these colonies had both, positive and negative aspects. Private business benefited in big profits coming from trade in sugar, tobacco, tin, petroleum and coal. Big possibilities of making money in commerce, industry, services and agriculture, as well as investments in the infrastructure attracted many residents of the Netherlands. After World War I the number of Dutch people who came from Europe was about 90,000. On the other hand for the state it ment a huge cost of maintenance and wars (particularly costly was the sultanate of Aceh war), while it only marginally participated in profits. The situation of the Netherlands treasury had improved only after the tax reform of 1908.

At the end of the 19th century some part of the Dutch society in the Netherlands began to consider the moral aspect of the Dutch exploitation of the Far East colonies what led to conclusion that the state had a serious debt to those colonies. It was calculated that the state profit was about 1.5 billion guilders. This is how the so-called “ethical policy” originated. New policy ment necessity of improving the situation of the local population by extending education, health care, improving communication, establishment of a modern system of administration of justice, etc. It was not without good calculation however as a better situation of the local people was beneficial for the sale of Dutch goods.

Interesting note:

In spite of intensive commercial contacts with its colonies the North Netherlands for a long time didn’t see the need to modernize its fleet by the replacement of sailing ships on the steamers. Goods were brought in regularly, so there was no reason to hurry up. In 1858 the Dutch merchant fleet consisted of 2,397 sailing ships and only 41 steamers, and in 1900 still 432 sailboats were in use. But there were also logistic reasons for it. Steam engines needed coal and supply-stations on the route to and inside Indonesia. These stations required service and protection of other ships. Hard work conditions made difficult to get crew. What is more – the coal ships had to return empty as were too dirty to carry food like tea, café, rice, spice, etc. So on distant routes sailing was cheaper than steaming. In the photo: ship sailing to colonies.

In spite of intensive commercial contacts with its colonies the North Netherlands for a long time didn’t see the need to modernize its fleet by the replacement of sailing ships on the steamers. Goods were brought in regularly, so there was no reason to hurry up. In 1858 the Dutch merchant fleet consisted of 2,397 sailing ships and only 41 steamers, and in 1900 still 432 sailboats were in use. But there were also logistic reasons for it. Steam engines needed coal and supply-stations on the route to and inside Indonesia. These stations required service and protection of other ships. Hard work conditions made difficult to get crew. What is more – the coal ships had to return empty as were too dirty to carry food like tea, café, rice, spice, etc. So on distant routes sailing was cheaper than steaming. In the photo: ship sailing to colonies.

19th CENTURY – TOWARDS INDEPENDENCY

At the beginning of the 20th century black clouds began to collect over the Dutch rule in the Dutch East Indies. It was connected with the awakening of national consciousness and the rise of anti-imperialist and revolutionary sentiment (as the echoes of the October Revolution of 1917). A big impact on it had economic and social changes in this area. Feudal relations were replaced by capitalism and industrial development led to the birth of the bourgeoisie and the proletariat, which both began to organize themselves in different political structures. In 1927 the Indonesian National Party was founded.

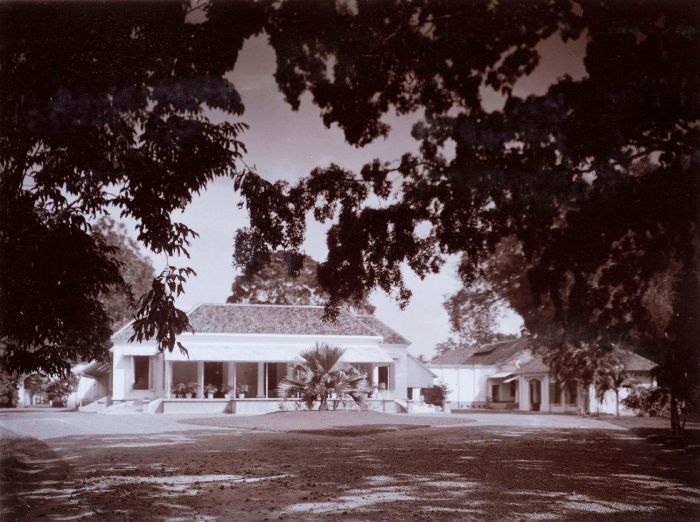

Dutch colonial residence

Emancipatory tendencies of the Indonesians met with strong resistance of the colonial government, representing interests of big Dutch capital, having there a flourishing business. Although some political reforms were introduced, strict control over colonies by metropolis was maintained. Every action against the colonial authorities (like uprising in 1926 on Java and in 1927 on Sumatra) was severely punished by imprisonment, deportation to penal camps, and even by death penalty. In this situation Indonesians began to contribute to Japan, which was seen as a liberator (on the eve of World War II Japan intensified economic expansion in the archipelago).

The Dutch East-Indies in 1941.

After the outbreak of World War II Dutch Indies became the site of the war with Japan. The war was declared by the Netherlands in December 1941, in response to Japanese request which had been rejected by Dutch government in exile. Since 1942 Japanese army successively occupied Dutch possessions, what led to the surrender of the Royal Dutch-Indian Army, signed on March 9, 1942. Since this moment situation of the Dutch population became dramatic. Hollanders were improsoned in camps and soldiers were forced to slave labor. Several thousand civilians and prisoners did not survive it.

Capturing of the Governor-General Tjard van Starkenborgh Stachouwer, 1942

Some Indonesians, including the late President Sukarno, saw in the Japanese reign a chance to gain independence, which they eventually did. Military defeat of Japan led to recognition of the independence of Indonesia which was proclaimed on August 17, 1945.

The Netherlands did not want to come to terms with the loss of this colony for a long time and tried to restore the former status quo with the military force. First attempts to resolve the problem were made however by negotiations and the peace treaties. One of them provided a new status quo, based on the concept of a federation called the United States of Indonesia (a part of the Kingdom), consisting of the Republic of Indonesia (Java, Madura, Sumatra) and Big East (Borneo and other islands under the direct control of the Netherlands). The relevant agreement was signed on November 15, 1946, in Linggadjati, but it did not satisfy any of the sides. (The Big East and the Moluccans voted to stay in the Kingdom as they did not want to come under the Javanian rule.)

Dutch soldiers controlling women of Batavia 1946

Struggle for freedom (fragment) the Japanese surrender to de Indonesian resistance.

In subsequent years (1947, 1948) the Netherlands launched two military interventions but despite signing new treaties had not been able to stop emancipation of Indonesia. The last formal link between the Kingdom of the Netherlands and the Republic of Indonesia (established on January 5, 1949) was a Dutch-Indonesian Union (signed on May 7, 1949), which gave the Netherlands a decisive control in foreign policy, finance, and military power in the western New Guinea. It was then as Batavia was renamed to Jakarta, which became the capital of the republic. The Union was broken by Indonesia in 1954, and in 1957 the Dutch property (state and private) had been nationalized.

The longest battle fought by the Netherlands was to keep control over western New Guinea, which led in 1960 to breaking off diplomatic relations between the countries.

Dutch New Guinea, 1916

In 1961 the disputed area was annexed by the Indonesians. In 1962 it was handed over to the UN interim administration to be in 1963 incorporated into Indonesia as the West Irian. Since the late ’60s, especially after the fall of Sukarno, relations between Indonesia and the Kingdom of the Netherlands began to normalize, as was evidenced by the visit of Queen Juliana in 1971.

The legacy left behind the Dutch rule in this area is huge, but perhaps more in the material heritage. This topic has been discussed separately in “The colonial legacy” chapter. It should be pointed out in this place however that the Dutch were the factor unifying various kingdoms of ancient East India, and the territory of modern Indonesia coincides with the former Dutch India.

Bandung, De “Groote Postweg Oost” – a long road built by the Dutch

Read also: A letter from a colony

Photos: Wikimedia Commons, Collectie Tropenmuseum