The return of the Royal Navy should have been a joyful day. But the walk through the devastated city to the Parkkade in Rotterdam (with the view on the destroyed port installations) made the thoughts very bleak.

Then the image of the returning fleet, once the “Dutch proud”, was unforgettable.Those rusted and dented ships were just leftovers, only a shadow of the glorious past. Both Queen Wilhelmina and audience fell into deep silence. That day everybody realized in his mind that he had awakened in q uite another country. No glorious stories followed but a period of harsh reality. The period of the “re-building” was one of great austerity and hard. Wages in the Netherlands were too high to die on, but too low to live on. A deep poverty, like in the 30s, now surpassed the entire population. It Seemed it was the first time after May 5, 1945 [the German surrender in the Netherlands] the painful reality was seen and felt. The euphoria of the renewed freedom extinguished. Problems were huge in the ransacked and totally neglected land. On the picture: queen Wilhelmina in Rotterdam, 1945.

uite another country. No glorious stories followed but a period of harsh reality. The period of the “re-building” was one of great austerity and hard. Wages in the Netherlands were too high to die on, but too low to live on. A deep poverty, like in the 30s, now surpassed the entire population. It Seemed it was the first time after May 5, 1945 [the German surrender in the Netherlands] the painful reality was seen and felt. The euphoria of the renewed freedom extinguished. Problems were huge in the ransacked and totally neglected land. On the picture: queen Wilhelmina in Rotterdam, 1945.

Almost literally everything had to be restored. City centers (as in Rotterdam, in Arnhem, in Middelburg, etc.) had to be totally rebuilt, the ports and the factories (totally destroyed and also looted), infrastructure (roads, waterways, airports, railways, etc.) had to be partly rebuilt. For the reconstruction of the country lots of money was needed. That money had to be borrowed. So after the investment was done, for a period, the profit from those investments was needed to repay the loans. There was no time for discussions by hotheads; working hands were needed “at the tools”. Furthermore pensions had to be paid to a generation which in the 30-ties (financial crises) and 40-ties (wartime) did not pay or paid insufficient premiums.

The returned boys “reconstructing” Rotterdam (read Maastrichter Star).

The returned boys “reconstructing” Rotterdam (read Maastrichter Star).

Then, in the late 40-ties and early 50-ties, ten-thousands of Dutchmen and “repentis” (Indonesians) arrived to the Netherlands from Indonesia because that country proclaimed independence and nationalized all Dutch (private and state) properties. To make matters even worse, in the stormy night of 1st February 1953 sea water broke through the for years neglected (crisis of the 30-ties, the war of the 40-ties) dikes and the Netherlands suffered much from the floodings.

Then came the 60-ties and the Netherlands became in almost all aspects a renovated and modern country. Most dik es had been renewed, the Marchal loans repaid to the USA and the new fellow countrymen absorbed. A new generation arose, demanding their rights. It was the message of the new era. The churches began to be empty (care should be a civil-right, so the state has to do it), unions had changed, all social justice had to be completed, carefull consultation and participation must be normal; it all changed all political parties (the “poldermodel” came in use). Further, the prosperity grew rapidely. Some example: a 19-year old boy used to earn (ca 1964) about 100 guilders a week, then went into military service, was payed 1 to 1.80 guilders per day and after returning to normal life, 22-years old, he started earning ca. 800 guilders a month! In the picture: Young Dutchmen in the late 50-ties (first from right: Author).

es had been renewed, the Marchal loans repaid to the USA and the new fellow countrymen absorbed. A new generation arose, demanding their rights. It was the message of the new era. The churches began to be empty (care should be a civil-right, so the state has to do it), unions had changed, all social justice had to be completed, carefull consultation and participation must be normal; it all changed all political parties (the “poldermodel” came in use). Further, the prosperity grew rapidely. Some example: a 19-year old boy used to earn (ca 1964) about 100 guilders a week, then went into military service, was payed 1 to 1.80 guilders per day and after returning to normal life, 22-years old, he started earning ca. 800 guilders a month! In the picture: Young Dutchmen in the late 50-ties (first from right: Author).

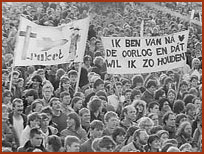

The 60/80-ties were the period of large demonstrations. Against the war in Vietnam, for education, against nuclear arms en energy, etc. Those against the cruise missiles to be positioned in the Netherlands brought almost 1 million people to The Hague. That generation used slogans as: “We are born after the war – we donot want to change that!” and “I prefer a Russian in the kitchen rather than a rocket in my garden”. It was the last demostration of a generation that became mature in the 60-ties that made themselves really audible. The “babyboom or after ’45-generation of students (born just after the war), was not only absorbed by domestic situation however but also observed again carefully what was ha ppening abroad. For example, the uprise in Hungary made a deep impression: “Hungary, we are with you!” was the yell of the protesters on the streets and in front of the eastern embassies. The poor people that escaped from Hungary, refugees, are now fully absorbed into Dutch society. Many “students” of the ’45-generation went also, in 1968, to Prague to see what was going on there. They were deeply shocked by the Warsaw Pact troops’ invasion. There was great respect for the way the Czechs endured their fate. Many of them (generation ’45) had tears in their eyes when, unfortunately, much later ex-leader of the Czech communist party Alexander Dubček came for the first time into the EU parliament and received a standing ovation. (He was the president of Czechoslovakia that introduced “communism with a human face” – so he gave hope, in the 60-ties). In the picture: anti-cruise missile protests.

ppening abroad. For example, the uprise in Hungary made a deep impression: “Hungary, we are with you!” was the yell of the protesters on the streets and in front of the eastern embassies. The poor people that escaped from Hungary, refugees, are now fully absorbed into Dutch society. Many “students” of the ’45-generation went also, in 1968, to Prague to see what was going on there. They were deeply shocked by the Warsaw Pact troops’ invasion. There was great respect for the way the Czechs endured their fate. Many of them (generation ’45) had tears in their eyes when, unfortunately, much later ex-leader of the Czech communist party Alexander Dubček came for the first time into the EU parliament and received a standing ovation. (He was the president of Czechoslovakia that introduced “communism with a human face” – so he gave hope, in the 60-ties). In the picture: anti-cruise missile protests.

And then there were the Poles. The Dutch teacher unions gathered in Rotterdam to discuss the government re form of the education system. During that meeting the message came from Poland – the first Polish independent trade union “Solidarity” called for support and Lech Walesa was the one who was named. His record was viewed immediately. The teachers strike was called off; the Board was authorized to use strike funds to support “Solidarity”. Later it became clear: these Poles took the first stone out of the wall dividing Eastern and Western Europe. The cry: “Poland what are you waiting for” was answered. That was a book, famous in that time, called “Polen waar wacht ge op…” about the uprise in Warschau against the Germans in 1944?), written by Philip Gibbs. That became the slogan used in demonstrations in front of the Polish embassy. In the picture: a Philip Gibbs book: “Polen waar wacht ge op…”.

form of the education system. During that meeting the message came from Poland – the first Polish independent trade union “Solidarity” called for support and Lech Walesa was the one who was named. His record was viewed immediately. The teachers strike was called off; the Board was authorized to use strike funds to support “Solidarity”. Later it became clear: these Poles took the first stone out of the wall dividing Eastern and Western Europe. The cry: “Poland what are you waiting for” was answered. That was a book, famous in that time, called “Polen waar wacht ge op…” about the uprise in Warschau against the Germans in 1944?), written by Philip Gibbs. That became the slogan used in demonstrations in front of the Polish embassy. In the picture: a Philip Gibbs book: “Polen waar wacht ge op…”.

It is clear that these feelings and developments had an impact on the Dutch society. These positive emotions are indeed followed by negative ones. (The revolting generation of the 60-ties felt silent as job and family made priorities different). After that their attention was taken to the banking crisis in Iceland, followed by those in Ireland, Greece, Spain and Portugal. Not mentioning the situation in Cyprus, Italy and Slovenia. Those events, and only the financial ones are mentioned above, created in some part of Dutch society skepticism towards the European Union. This skepticism is interpreted differently by each political party and there are quite a few of them in the Netherlands!

The polder model – As a result of the demonstrations of the generation 60’ in the Netherlands, slowly, the way of ruling has changed. Important social laws were first discussed in “tripartite” meetings. That means that ideas were first presented and modified by representaves of trade unions, industry and the cabinet and only after their agreement a new bill was made and send then to the parliament.

Photo: Wikipedia, Historical Boys’ Clothing, private archive, other sources