EARLY MIDDLE AGES

1. The state of Franks

Soon the Frankish Merovingian dynasty took control over the entire Roman Gaul (today called France) and became the ruling class over the Romanized Celtic tribes who lived there. Unlike the Eastern Franks, the western Franks in the south did not force their language (Frankish) upon the Romanized Celts, choosing Latin for the official language. This was the language that they both had learned from their former rulers. And from the mix of Latin and the Old Frankish (having the structure and some words of Old Dutch) emerged as the speech of the southern Celts. Old Dutch (also called Old Frankish) didn’t disappear however and was still in use in the north but mainly as a spoken language, written only scarcely. The boundary between Old French and Frankish (Old Dutch) runs from the south of Limburg to (present) Boulogne (Dutch: Bonen). Because the southern Netherlands (now Belgium) went few times its own way under a Catholic French-speaking elite, this border moved in the course of history to the north.

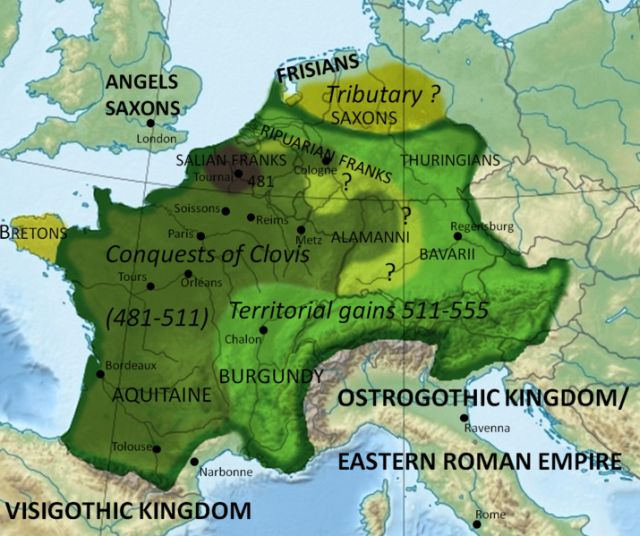

Frankish empire 481 – 555

With the Great European Migration and consequent departure of the Roman legions, Europe became significantly less safe. The trade languished so the use of money disappeared almost entirely. Tax could therefore hardly be raised so the Frankish kings initially could not finance an army. This meant that the state organization had to be based on different way. For the (Germanic) Franks it was not a significant problem. They were used to be organized in small units (homesteads). These homesteads pulled together to deal with local problems, while the entire tribe looked after the collective interests. This system was introduced in the entire Frankish empire. The lower nobility (barons, appointed by the higher nobility) ruled over clusters of villages, the higher nobility (appointed by the imperial nobility) controlled the shires, and the imperial nobility (appointed by the king) controlled the lands. The imperial nobility consisted of barons, who were responsible for the administration only; counts that also took care of law and raised armies; and dukes, responsible for the state boundaries, who also were in command of state armies. Initially, these were functions to which one should be appointed, but when, especially after Charles The Great (who died in 814), the kings were weaker and preferred the luxurious court life, these functions became gradually inherited. In the most simply way one could say that the high nobility became independent rulers who saw their “fiefdom” as heritage, so their possessions became more or less independent states. Seven of these “states” in the Netherlands are today the provinces: Friesland, Gelre, Groningen, Holland, Oversticht, Sticht and Zeeland. The Sticht (means diocese) was in the beginning one diocese with the Oversticht. These lands did not border to another and later became separate provinces: Sticht is, today, the province of Utrecht and Oversticht the province of Overijssel. Holland, Zeeland and Western Frisia grew practically into one state. That mighty Holland was officially called: “Holland, Zeeland and West-Frisia”. The modern name of the province of Gelre is Gelderland. In the future these seven united states formed the famous republic of the Netherlands – the Republic of the “Seven United Provinces”. On the picture: a Frankish helmet,7th century.

(appointed by the king) controlled the lands. The imperial nobility consisted of barons, who were responsible for the administration only; counts that also took care of law and raised armies; and dukes, responsible for the state boundaries, who also were in command of state armies. Initially, these were functions to which one should be appointed, but when, especially after Charles The Great (who died in 814), the kings were weaker and preferred the luxurious court life, these functions became gradually inherited. In the most simply way one could say that the high nobility became independent rulers who saw their “fiefdom” as heritage, so their possessions became more or less independent states. Seven of these “states” in the Netherlands are today the provinces: Friesland, Gelre, Groningen, Holland, Oversticht, Sticht and Zeeland. The Sticht (means diocese) was in the beginning one diocese with the Oversticht. These lands did not border to another and later became separate provinces: Sticht is, today, the province of Utrecht and Oversticht the province of Overijssel. Holland, Zeeland and Western Frisia grew practically into one state. That mighty Holland was officially called: “Holland, Zeeland and West-Frisia”. The modern name of the province of Gelre is Gelderland. In the future these seven united states formed the famous republic of the Netherlands – the Republic of the “Seven United Provinces”. On the picture: a Frankish helmet,7th century.

2. The awakening of Holland

In a time called the Migration Period (4th – 8th centuries) the northern parts of the present Netherlands, Frisia, also received an influx of new immigrants and settlers, mostly Saxons, but also Angles and Jutes. They took the place after its former inhabitants, the Frisians. Old Frisia, since 4th century friendlier for any settlement again, was quite a large coastal region which embraced northern Frisia in the south of Denmark, eastern Frisia in present Germany, central (Lauwers) Frisia in the northern parts of the present Netherlands and western Frisia (in the west of the Netherlands). In other words – the country had stretched from the south of present Denmark along the coast of the North Sea (which was called in old times the West Sea or Frisian Sea) to the north of present Belgium (Flanders). This extended Frisian territory is sometimes referred to as Frisia Magna (or Greater Frisia).

According to Frankish chronologies in the 7th and 8th century this area was the kingdom of the Frisians, ruled by kings Alde gisel and Redbad (650–734), with Utrecht (Traiectum) as a the centre of power. Conquering this land took Franks a lot of time. The local people didn’t care much about who ruled over them as long as they didn’t interfere much into their daily life. But after some time that situation had changed. It happened so because the faraway ruler, Charles the Great, was crowned by the Catholic Church as Emperor and he wanted them to be baptized. The southern parts of Frisia (Rhineland = present Holland and present Utrecht with the mix of former Batavians, Caninefates and Frisians), that had been already absorbed smoothly by Franks, became unhappy and got sympathy for the “free” Frisians”. So it was a difficult job to incorporate the remaining parts of Frisia and their Saxonian friends into the Frankish empire. On the map: Magna Frisia in 716.

gisel and Redbad (650–734), with Utrecht (Traiectum) as a the centre of power. Conquering this land took Franks a lot of time. The local people didn’t care much about who ruled over them as long as they didn’t interfere much into their daily life. But after some time that situation had changed. It happened so because the faraway ruler, Charles the Great, was crowned by the Catholic Church as Emperor and he wanted them to be baptized. The southern parts of Frisia (Rhineland = present Holland and present Utrecht with the mix of former Batavians, Caninefates and Frisians), that had been already absorbed smoothly by Franks, became unhappy and got sympathy for the “free” Frisians”. So it was a difficult job to incorporate the remaining parts of Frisia and their Saxonian friends into the Frankish empire. On the map: Magna Frisia in 716.

After the death of Charles the Greats son, Louis I the Pious, the Frankish empire had been divided into three parts – according to The Treaty of Verdun (843). Each of his three sons: Lothair I, Louis the German and Charles the Bald, got one and they became kings of their own kingdoms (the imperial crown went later to the eastern division). The division of the empire was as follows:

- the western part included the south of the Netherlands and became the cradle of France

- the eastern part included some parts of the Netherlands (like eastern Frisia), what became the origin of Germany

- the central part embraced most of the present Netherlands, Elsach, Lothar, Swiss, Italy, Luxembourg, etc.

Division of the Frankish Empire after the Treaty of Verdun

The central part was very elongated on a north-south direction and narrow from east to west, and so hard to maintain and defend. In the course of the later history eastern and western kingdoms incorporated some parts of this vast territory and thus the central kingdom (a Lothair’s dominion) ceased to exist. The northern part of the kingdom, Lorraine (an area of French and German competition, up to the 20th century!) was split into two separate principalities – Lower Lorraine and Upper Lorraine. Since the 12th century the Lower Lorraine is called Netherlands (terrae inferior – lowlands).

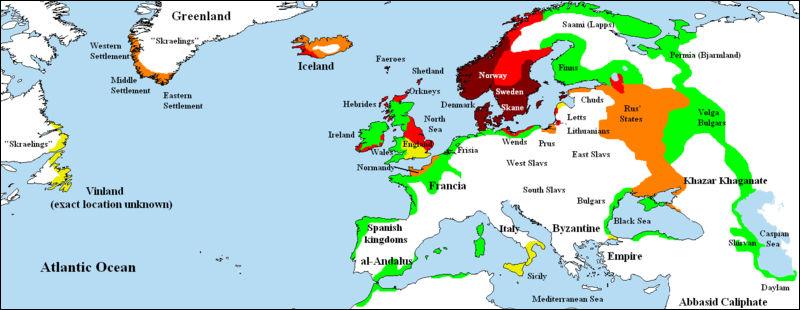

3. Viking invasions

At the end of the reign of Charles the Great the Netherlands were visited by the Vikings who invaded Frisia in the 9th and 10th centuries. The first time they came as traders, but seeing how weak the northern part of the (former) Frankish empire was, they returned in a less friendly way. (Although Vikings never settled down in these areas, they did set up long-term bases and were even acknowledged as lords in a few cases. One of the most important Viking families in the Low Countries was that of Rorik of Dorestad (who lived on the former island of Wieringen) and his brother, the “younger Harald”. It is difficult to judge these “foreigners” because most information comes from monks that didn’t like Vikings for their refusal of Christianity. Furthermore they were, in many cases, related with the Frisians and loving the same pagan gods like the local people in the Low Countries. So hostility with the cloisters grew quickly.

Vikings invasions

Getting no support from their kings/emperors the counts of Rhineland (Frisian line) started to organize and unite the counties around them. They formed groups of ships (committees, the first Dutch fleets!) to defend their coasts. They became de iure independent because their overlords broke the oath of defensive support. In this way Holland was born. When much later the German emperor sent an army against them, they defeated it (near Vlaardingen) and showed that way their military independence and strength defacto. But they never claimed a formal independency however, avoiding a formal argument for war (prefering trade). So the beginning of Holland was, technically, just a shift of power from central Frisia to west Frisia/Rhineland. The first counts of Rhineland were kings or dukes of Frisia. The first of this family tree, as far as we know, was born ca. the year 600, the last one (as ruler) ca. 700 years later.

II HOUSE OF BURGUNDY

1. Development of provinces (9th – 14th centuries)

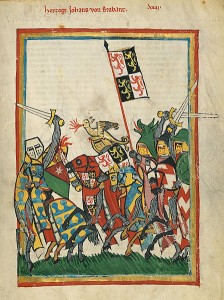

From the 9th century there were big political changes in the Charles the Greats (and his successors) empire. From the former royal officials (counts) and nobility em erged a class of feudal lords, which formed numerous feudal states. They were connected by network of complex feudal dependencies but also led numerous wars with each other. It led to a strong territorial fragmentation resulting in more powerful principalities. In Lower Lorraine and its outskirts counties were created in the 10th and 11th centuries: Lower Lorraine (from the 12th century – Netherlands), Flanders, Holland, Brabant, Limburg, Luxembourg, Gelderland, Cleves, Hainaut and Bishoprics Leodium, Cambrai and Utrecht. Along the shores of the North Sea Friesland was streched, formally a county, which fiercely defended its “freedom”, constantly threatened by Holland and Utrecht. The 12th and 13th centuries were a period of diverse struggles and conflicts between these states, which highly reinforced Holland. United with Zealand and Hainaut, Holland aspired to play a major political role in Europe. On the picture: John of Brabant, Codex Manesse, 1305-1315.

erged a class of feudal lords, which formed numerous feudal states. They were connected by network of complex feudal dependencies but also led numerous wars with each other. It led to a strong territorial fragmentation resulting in more powerful principalities. In Lower Lorraine and its outskirts counties were created in the 10th and 11th centuries: Lower Lorraine (from the 12th century – Netherlands), Flanders, Holland, Brabant, Limburg, Luxembourg, Gelderland, Cleves, Hainaut and Bishoprics Leodium, Cambrai and Utrecht. Along the shores of the North Sea Friesland was streched, formally a county, which fiercely defended its “freedom”, constantly threatened by Holland and Utrecht. The 12th and 13th centuries were a period of diverse struggles and conflicts between these states, which highly reinforced Holland. United with Zealand and Hainaut, Holland aspired to play a major political role in Europe. On the picture: John of Brabant, Codex Manesse, 1305-1315.

Characteristic feature of these small dutch states – not seen anywhere else in Europe – was a very early development of parliamentarism. Reduction of income as a result of donations, sale or pledges forced feudal lords to raise money (or support in matters of succession) in return for the privileges granted to representatives of the nobility and towns. The earliest influence on the state affairs got the residents of Brabant – already in 1312, thanks to the so-called “Charter of Cortemberg”. In the Holland, since the mid-14th century, council meetings were held (in the knightshall in the Hague), consisting of representatives of the count, the nobles and the cities. Interestingly, participation of townspeople in these meetings was very significant and even gradually they became predominant. (It was favored by enrichment of the cities and impoverishment of the rulers.) This is how the provincial “States” emerged in the 15th century, severely limiting the power of the counts and dukes.

Battle of Courtrai (Kortrijk), 1302 – Flemish burghers defeating the army of Philip IV the Fair

2. The House of Burgundy rule (1385 – 1482)

At the end of the 14th century Dutch states began to be heavily influenced by the Duchy of Burgundy, whose rulers had an ambitious plan to create there a modern and well-managed monarchy. Merging those states was done partly by marriages, partly by conquest. This policy was initiated by Prince Philip the Bold and continued by his successors John the Fearless, Philip the Good and Charles the Bold. Within a hundred years they managed to concentrate in their hands Flanders, Brabant, Limburg, Luxembourg, Holland, Zealand, Hainaut, Namur and Gelderland. Only disobedient Friesland efficiently resisted those attempts.

The reign of the House of Burgundy was for the Netherlands not only beneficial in economy and culture, but also created the basis for political system that has survived for several centuries. It was at this time that the stadtholder (stadhouder = governor) office was created. His mission was to rule in the name of the Duke of Burgundy (note that the Burgundy and the Netherlands were two separate territories with Lorraine between them). Stadholders were appointed by the provinces and the whole country was controlled by the stadholder-general. Power was exercised by the States-Provincial, and from the mid-15th century the States-General, consisting of the representatives of the States-Provincial. Initially they were convened by the Duke of Burgundy, but gradually gained more independence and convened spontaneously. Their significance increased after death of Charles the Bold (1477). This death opened a new chapter in the history of the Netherlands. Charles’s daughter, Maria, married Maximilian Habsburg of Austria (1477), and in 1482, after the birth of their son Philip, she died, so the rule over the Netherlands went to the Habsburgs.

On the map: Burgundy in 1467-1477.

3. Economy, society

Despite the Viking raids and harassing the area by floods, Holland in Early Middle Ages experienced a rapid economic development. Draining the marshland, initiated in the 12th and 13th centuries, resulted in widening the area of crops, and Dutch agricultural productivity was very high. Thanks to trade and crafts the towns grew in power very quickly (Netherlands were an important sea and river trade route). Significantly grew also the importance of a cloth and weaver industry (mainly focused in the Flemish cities). In the 15th century there was an intense process of urbanization, especially in the Northern Netherlands. The city of Utrecht had a population of about 40 000 inhabitants. Fisheries development led to expansion of the fleet. This does not mean, however, that these areas had not experienced any social conflicts, which clearly was showed in the next century.

An altarpiece with the St Elizabeth’s Day Flood 18-19 November 1421